Selection of my research

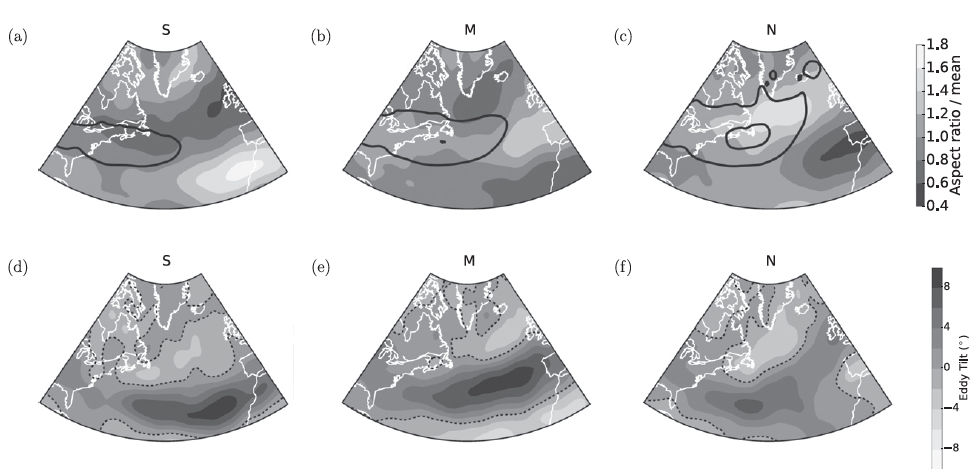

Jet shifts in latitude are modulated by growth of stormsThe positions of the midlatitude jet, averaged over the North Atlantic sector, can be categorised into three main clusters, referred to as the South, Middle and North jet regimes. Using reanalysis data (global observations stitched together by the ECMWF model) we found that these jet regimes are highly correlated with features of eddy lifecycles, including their growth rate, vertical tilt, horizontal tilt and shape. We found that the preferred regime cycling from S to M to N to S, is often related to the explosive cyclone growth upstream of the jet fluctuations. |  |

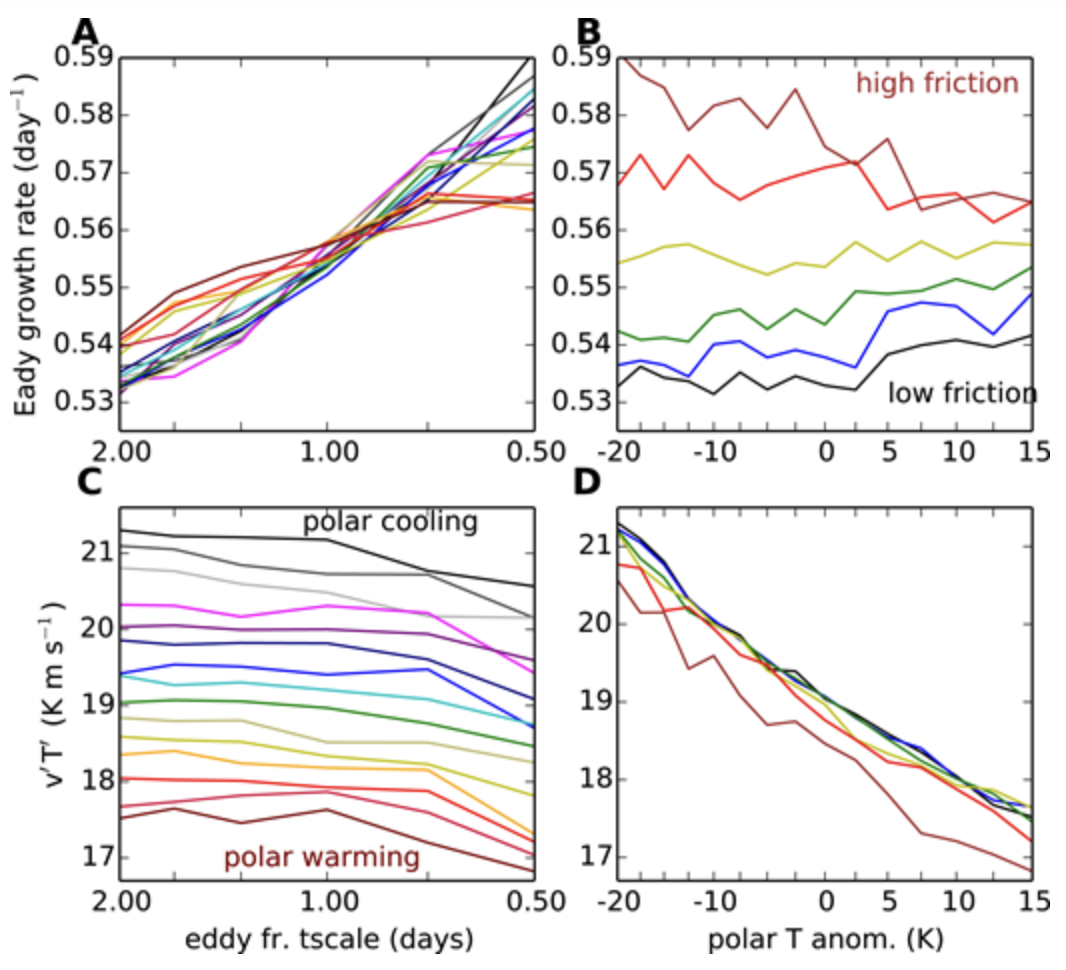

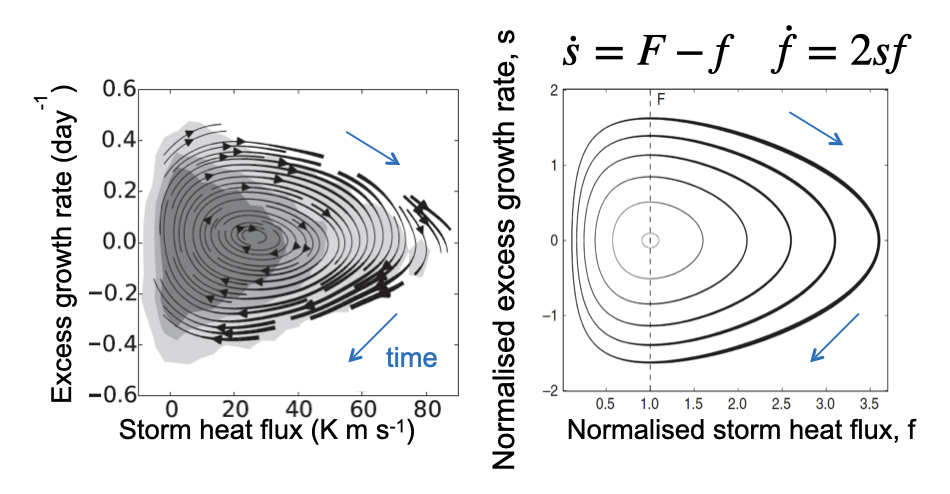

| The response of storm tracks to temperature changes can be large even when their growth rate remains largely unchanged (multilayer dry global circulation model, PUMA)It has been noted in observational studies that on seasonal and longer timescales, storminess is very sensitive, even though its growth rate (related to the temperature gradients) is not. To investigate this seemingly counterintuitive phenomenon, we used the steady state of the nonlinear oscillator model discussed below and in (Ambaum and Novak 2014). According to this pen-paper model, the growth rate is maintained by the eddies, so any change to the its replenishing forcing will be counteracted by an increase in the eddy activity. Conversely, when eddy dissipation (e.g. friction) is modified, this will be counteracted by changes in the temperature gradients and thus the eddy growth rate (evidently the storms may be more explosive, but their time-mean intensity is largely unchanged due to their fasted dissipation. This highlights the difference between mean weather and extreme weather changes). This hypothesis was confirmed in a dry global circulation model, which was run with multiple times with constant external parameters until its statistical steady state (model is run for decades until the circulation equilibrates) was reached. This experiment also showed some secondary importance of barotropic processes (linked to the decay of eddies) for this balance, which need to be considered in more comprehensive models. |

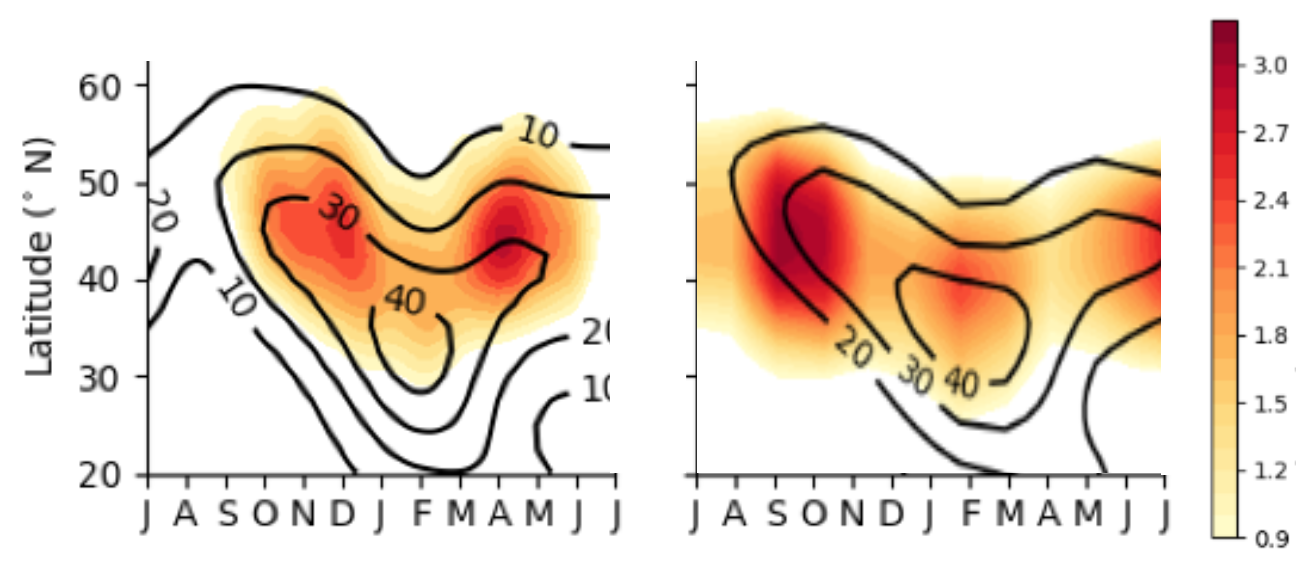

A model with no vertical structure can reproduce observed nonlinear suppressions in winter storminess (modelling using a one-layer barotropic model)Understanding the formation of the suppression has been in dynamicists’ minds now for decades, because it does opposite to what linear theory predicts. Recently idealised modelling efforts has proven insightful for shedding more light on this phenomenon. We joined this effort by showing that even one-layer (barotopic) model can reproduce this suppression and quantified the processes necessary for its formation. |  |

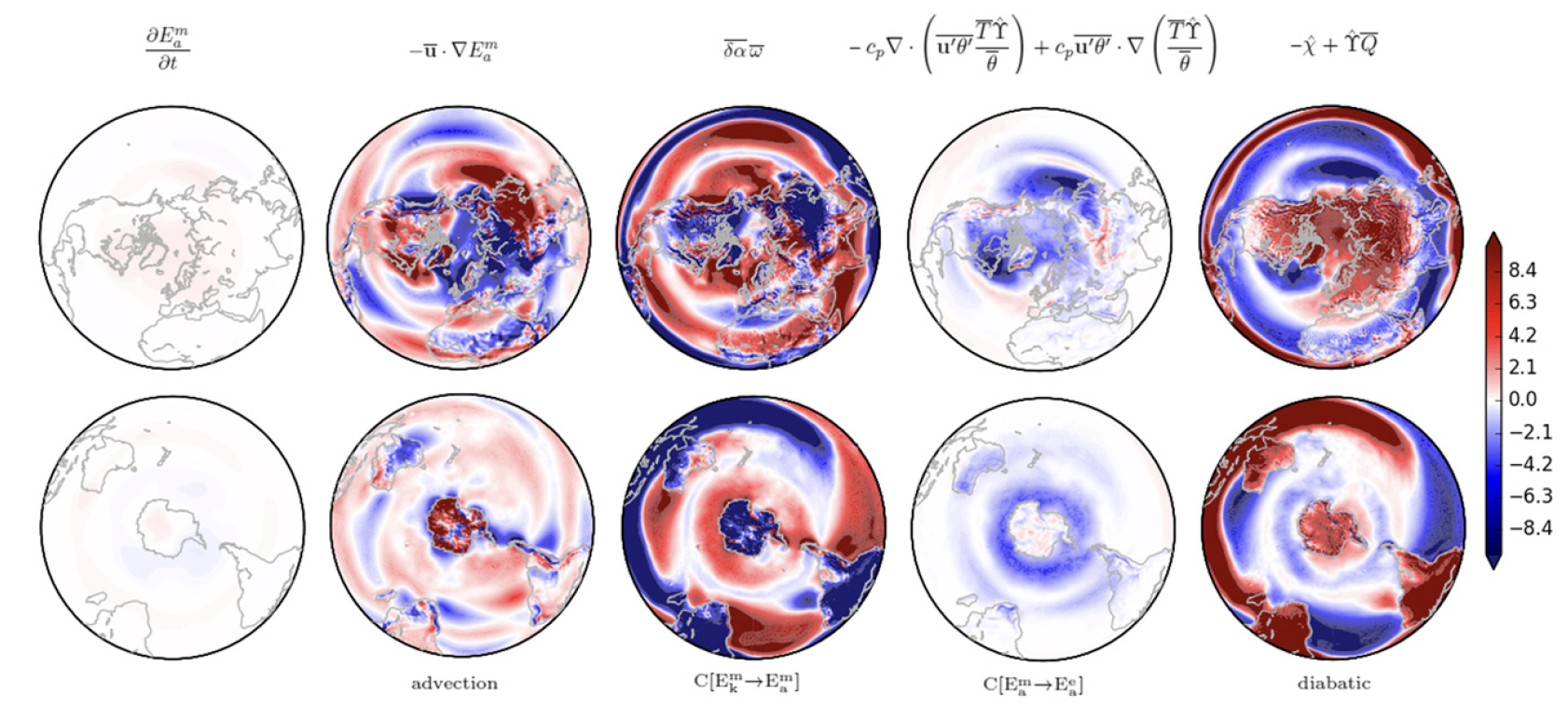

| Ability to diagnose local potential energy available for turbulent motions locallyEnergy currently used by atmospheric motions (kinetic energy, KE) and energy available to be converted into atmospheric motion (available potential energy, APE) sum to a total energy that has to be globally conserved in time. The usefulness of these energies for diagnosing properties of the circulation is greatly enhanced if considered locally, so that one can diagnose the processes that lead to their spatial-temporal changes. While KE density is easy to diagnose locally from the horizontal wind components, Lorenz originally defined APE as a global quality, and its estimates in the following research have mostly been approximations that curtailed research requiring precise estimates, such as energy budgets. We extended an often-overlooked derivation for a local APE density from the 1980s, to provide a new diagnostic that facilitates local APE diagnosis and offers precise calculations of the processes that modify it. |

Extreme storminess occurs on monthly timescalesThis is a fundamental property of the nonlinearly oscillatory relationship between the storminess and the sharp temperature gradients that give rise to storminess in the first place. Much the same as a biological predator-prey model where storminess feeds on the gradients until they are eaten up to the point they can no longer sustain new growth of storms. The subsequent reduced storminess then allows the gradients to build up again by (e.g. radiative) forcing and the cycle repeats. Borrowing concepts from dynamical systems, we developed a pen-and-paper model that describes this behaviour and models some of the detailed properties of the real atmosphere. |  |